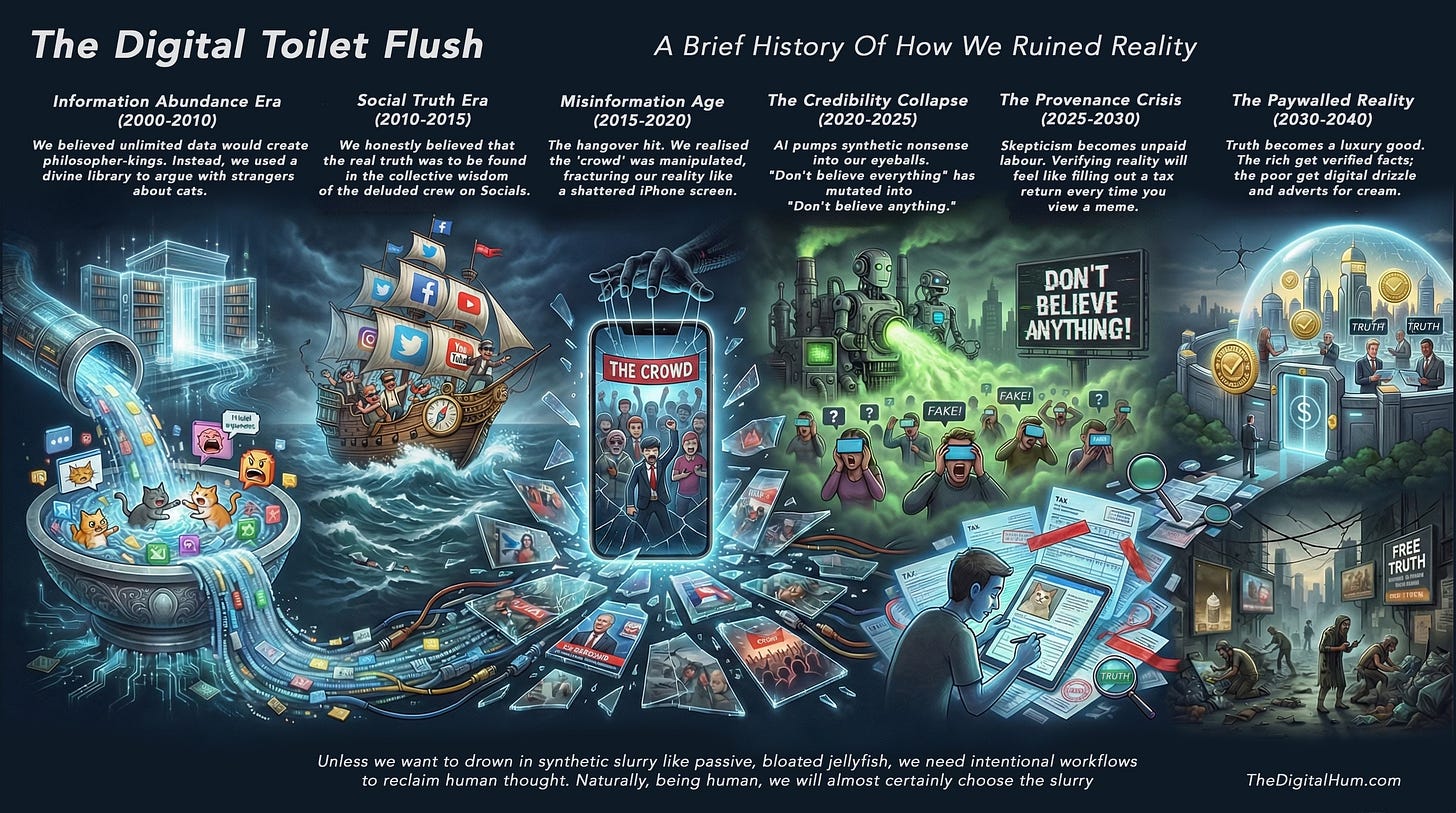

The Digital Toilet Flush

A brief history of how we ruined reality

Look around you. Not at the actual world, that frightening expanse of damp pavement and disappointing sandwiches outside your window, but at your screen. The glowing rectangle that dictates your mood, your politics, and whether you think the Pope has started wearing Balenciaga puffer jackets. It’s a screaming, chaotic bin fire of half-truths and hallucinatory nonsense.

In a fit of morbid curiosity, the sort of self-destructive impulse that usually ends with googling your own medical symptoms, I decided to sit down and sketch out a timeline hypothecating the trajectory of our digital lives from the turn of the millennium to the near future.

It maps the journey from naive optimism to our current state of epistemological vertigo with depressing accuracy. The result reads less like a history and more like a coroner’s report on truth.

Let’s stick on the rubber gloves and examine the corpse.

Remember the 2000-2010 “Information Abundance Era”? Bless. We were so cute back then, with our dial-up modems screeching like strangled cats. We genuinely believed that giving humanity unfettered access to all human knowledge via Google and Wikipedia would usher in a new Enlightenment. We thought “information wants to be free.”

It turns out information just wanted to be irritating, contradictory, and frequently hosted on pages illuminated by pop-up ads for enlargement pills. We imagined a nation of philosophers; we got a world arguing in YouTube comments about whether the moon landing was faked by Stanley Kubrick.

Then came the 2010-2015 “Social Truth Era.” This was the point where we decided that traditional media was too slow and stuffy, and that the real truth was to be found in the collective wisdom of the crowd on Twitter. “Pics or it didn’t happen” was the mantra.

We honestly believed that if enough people retweeted something, it became fact by sheer democratic brute force. It was like trying to perform intricate surgery using a consensus of people shouting directions from the pub car park next door.

Inevitably, this led to the 2015-2020 “Misinformation Age.” The hangover kicked in. We realised the “crowd” could be manipulated by algorithms, bad actors, and a well-timed meme featuring Pepe the Frog.

Reality fractured like a cheap windscreen hit by a pigeon. We retreated into echo chambers that felt comforting but smelled faintly of intellectual stagnation.

Which brings us to the current sewage pipe we are swimming in: “The Credibility Collapse” (2020-2025). Thanks to generative AI, deepfakes, and chatbots that hallucinate with the confidence of a mediocre Oxford graduate, we have reached the nadir. The old adage “Don’t believe everything you see online” has mutated into a nihilistic screech of “Don’t believe anything, ever, even if your own mother is holding it up in front of your face.”

We are being waterboarded with lukewarm nonsense. It’s the equivalent of wading through treacle wearing lead boots while someone throws custard pies at your eyes.

The timeline suggests we are currently pivoting into the “Provenance Crisis” (2025-2030). This is where the exhaustion sets in. Because nothing can be trusted on face value, everything requires a digital DNA test. We will spend our lives checking watermarks and authenticating chains of custody just to confirm that a photo of a cat is, indeed, a cat, and not a hyper-realistic render created by a bored teenager in Omsk trying to steal your banking details.

It’s skepticism as a full-time, unpaid job. It’s a miserable way to live, like having to chemically analyse your breakfast cereal every morning to ensure it’s not made of painted gravel.

Extrapolating this misery forward, we arrive at ‘The Authentication Economy’ (2030-2040). This is the truly dystopian bit that makes my stomach churn.

If establishing truth is expensive and exhausting, then truth becomes a luxury good. We are heading for “information apartheid.” The wealthy will pay handsome subscriptions for walled gardens of verified reality, news that actually happened, photos of real people, scientific papers written by humans.

The rest of us will be left outside in the digital favela, subsistence-farming on a diet of AI-generated slop, algorithmic hallucinations, and personalised propaganda designed to keep us angry and clicking on adverts for things we can’t afford.

It’s a grim forecast. It shows precisely why just riding the wave of technological progress like a passive, bloated jellyfish is a suicidal strategy. We need intentional workflows. We need to use these incredible tools to enhance human understanding, not replace it with a synthetic slurry.

We probably won’t do that, of course. We’re humans. We’ll almost certainly choose the path of least resistance right off the edge of the cliff. But it’s nice to know exactly how we’re screwed, isn’t it?

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go and lie face-down on the carpet and inhale the dust of a thousand dead weekends.